Life, Novels

JOVAN PEJČIĆ, LITERATURE AND CULTURE HISTORIAN, ABOUT TIMES AND SERENITY, HARMONIES OF LIFE AND WORK

We’ve Got Our Roots

One prepared for life, work and sacrifice by the St. Sava and Kosovo vow will forever stand above transient interests and daily calculations. Only words-symbols show the fullness of Being, strength of Name, beauty of Truth. Genuine Serbia speaks that language. The greatest day in the life of poet Milan Rakić, the one in Gazimestan in 1912, is still a measurement for all of us. Comedies are one-time and do not repeat, tragedies are permanent and return. Belgrade, with its ingenuity and fate, could not survive if it weren’t a natural and deep focus of literary imagination

By: Branislav Matić

Photo: Guest’s Archive

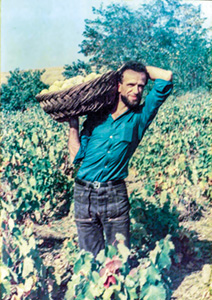

He knows. Where there is great effort, there are miracles. A wonderful, ancient sentence reaches heights with its depth. Pure language is a starting point for all spiritual golds, a background for transfiguration. If so, a new house can be built with old bricks. Genuine culture, which nations founded in God lean upon, requests great workers and subversive geniuses. Provided they are masters. The entirety of Serbiandom has always ticked in the Serbian South. He learned epic poetry from his grandmother, reading the world from his grandfather and father, refined singing from his mother. Such people cannot be degenerated even if they wanted to.

He knows. Where there is great effort, there are miracles. A wonderful, ancient sentence reaches heights with its depth. Pure language is a starting point for all spiritual golds, a background for transfiguration. If so, a new house can be built with old bricks. Genuine culture, which nations founded in God lean upon, requests great workers and subversive geniuses. Provided they are masters. The entirety of Serbiandom has always ticked in the Serbian South. He learned epic poetry from his grandmother, reading the world from his grandfather and father, refined singing from his mother. Such people cannot be degenerated even if they wanted to.

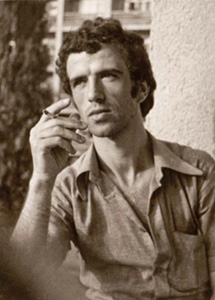

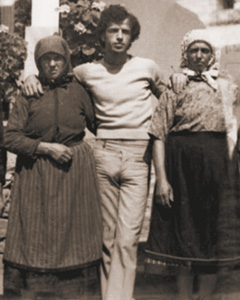

Jovan Pejčić (Bošnjace near Leskovac, 1951) – literature historian, critic, essayist, anthologist – in National Review.

Gifted Identity. When I was tempted to leave Serbia at the time I graduated at the university, my grandfather dissuaded me from doing so by saying: ”If God wanted you to live there, you would’ve been born there.” When, after completing my postgraduate studies, I decided not to return to my hometown and stay in Belgrade, father just said: ”Belgrade is ours.”

Fathers hand down to their sons: from grandfather to his successor, from my father to me. Like ethics, love for children and the homeland never grows old. I, therefore, do not see a difference between my grandfather’s and my father’s words, not even in their most remote, most mysterious dimensions, because it is the same feeling of the meaning of existence, the meaning of co-existence with your family and your nation, the same invitation to living in space and time, the same challenge with higher knowledge and national history. In short: confirming the gifted identity, in its entire ancientness and contemporariness. That identity is Serbian in every aspect: Serbian language, Serbian Cyrillic alphabet, entire Serbian culture – eternal Serbian fate.

By its roots and heights it has ascended to, the identity of the Serbian nation, therefore my identity as well, does not betray in any aspect, does not narrow, does not reduce the all-human horizon of validity. It is because its character is historical, it is not for daily purposes.

Nation under the Symbol of the Cross. When ”world powers” set off to cancel Serbia for the third time in the twentieth century, I stated my preference and attitude at the protest evening in April 1999 in the Serbian Writers’ Association. I entitled my speech: ”Singing of symbols – Serbia under bombs”. I am stating a part of it:

Nation under the Symbol of the Cross. When ”world powers” set off to cancel Serbia for the third time in the twentieth century, I stated my preference and attitude at the protest evening in April 1999 in the Serbian Writers’ Association. I entitled my speech: ”Singing of symbols – Serbia under bombs”. I am stating a part of it:

”Words-symbols – how difficult it is to grow up to them, how burdening it is to be under their authority! A symbol gives a name and celebrates, ascends into the depth, illuminates by descending, connects the land and the skies, consecrates the world. A symbol never passes and never grows sold – a symbol is a vow and shield, a votive shield, the shield of the Vow. He who has the Vow stands on the Mountain, with it man says – I. Only words-symbols express the fullness of Being, strength of Name, beauty of Truth. That is the language Serbia speaks. Can it not speak another language, or does not know how to, or does not want to? – shouts someone. I reply: Should we speak another language? I reply: I, in fact, do not know if those are Serbs speaking, or Serbian symbols talking through Serbs: Chilandar and Studenica, Žiča and Gračanica, Mileševa and Visoki Dečani, Patriarchy of Peć and the monasteries of Fruška Gora; Nemanja, Dušan and Lazar – Sava, Nikolaj and Justin; Kosovo and Topola – Miloš and Karađorđe; Čegar and Kolubara – Stevan and Živojin; Šumadija, Lovćen, Serbian South and Vojvodina – Vuk, Njegoš, Bora and Crnjanski; powers of God and laws of earth – Bošković, Tesla, Pupin, Milanković, Alas; nature and nation, history, word and criticism – Cvijić and Mokranjac, Višnjić, Ruvarac and Skerlić; the spirit of the world and soul of poetry – Knežević and Petronijević, Jefimija, Laza and Nastasijević...”

On the Stonepit of Heroism. Since Serbian fate has always been such in time, I can calmly say: those prepared for life, work and sacrifice by St. Sava’s and Kosovo vow, are eternally standing above transient personal, state and world tempests, above simple interests of politics, stirred with considerations, fears and daily calculations.

On the Stonepit of Heroism. Since Serbian fate has always been such in time, I can calmly say: those prepared for life, work and sacrifice by St. Sava’s and Kosovo vow, are eternally standing above transient personal, state and world tempests, above simple interests of politics, stirred with considerations, fears and daily calculations.

I learned it from my grandmother early, in an indirect way. While grandfather, father, mother, aunts, sisters were spending entire days in the field, I, as the youngest, spent time with my grandmother, listening to her stories and playing. Grandmother was a true stonepit of epic poetry. She knew the Kosovo and Uprising epics by heart, which she inherited from her unlamented brother without a grave, who disappeared in the Albanian Golgotha at the age of seventeen. She taught me my first lessons in history and poetry. I was infused with her narrations so much that the two of us spoke about everything in decasyllabic verse. I kept it to the very day.

While my grandmother introduced me to Serbian national history and legends, grandfather and father, in long winter nights, revealed the history of my homeland and mentality of local people. I learned that my birthplace was known already in the Nemanjić era; that Bošnjace, with its spiteful and rebellious character, attained the title of a free village under Turks, excluded from imperial taxes; that it became a municipal town after the liberation of Southern Serbia; that the Jablanica county office used to be in our churchyard.

Then: that the church in Bošnjace has lasted since mid-fourteen century; that it was burned and destroyed by the Turks many times, but always renovated by the villagers; that our church has kept an antimins consecrated with the cross of Patriarch Arsenije IV Šakabenta during his retreat from the Patriarchy of Peć to Srem, running from vengeful Ottomans; that priests read from original Gospel manuscripts to faithful people on holidays… (Miloš Milojević, reputable national worker, historian and travelogue writer, professor and director of the Leskovac Gymnasium at the time, took away the Gospel in early 1880s. Today, nothing is known about him, or the mentioned antimins.)

Then: that the church in Bošnjace has lasted since mid-fourteen century; that it was burned and destroyed by the Turks many times, but always renovated by the villagers; that our church has kept an antimins consecrated with the cross of Patriarch Arsenije IV Šakabenta during his retreat from the Patriarchy of Peć to Srem, running from vengeful Ottomans; that priests read from original Gospel manuscripts to faithful people on holidays… (Miloš Milojević, reputable national worker, historian and travelogue writer, professor and director of the Leskovac Gymnasium at the time, took away the Gospel in early 1880s. Today, nothing is known about him, or the mentioned antimins.)

I learned from my grandfather’s and father’s stories that the school in Bošnjace was founded in 1860, and that it has been working in the church for twenty years; later, when it got its own building, it was officially proclaimed a four-subject national school, where students learned national history, national poetry, calculation, and calligraphy, until the final liberation from the Turks.

In his stories, father stuck to events and their chronology; grandfather, however, found more important tradition, through which people built their spirit, their life, their country, and human actions that testified about spirit and tradition, traditional ethics.

That is how I remember them, father as a chronicler and grandfather as a moralist.

Where is mother? My heart starts singing when I think of fairytales she put me to sleep with, stories she made up for me when I was upset because of a bad dream, her whispery singing of songs and words, creating an echo of an elusive tone of love and specific, pious existential mysticism…

Initiation into Literature. With the passing of years, a moment of childhood frequently returns to my memory, which I tend to believe it perhaps crucially determined the direction of my life, emotional and intellectual determination, meaning of working in literature and on literature.

Initiation into Literature. With the passing of years, a moment of childhood frequently returns to my memory, which I tend to believe it perhaps crucially determined the direction of my life, emotional and intellectual determination, meaning of working in literature and on literature.

I started reading early, asking questions about what I had read, writing my observations in books. In the place I gained my first literary knowledge, in Bošnjace, there was a small library from which, it seems, I rarely exited. There, as a seventh-grade student, I met Boško Pavlović, my distant thirty-year-old cousin – he, I know it now, took me from the chaos of my reading hunger into the universe of all-literature and thinking about it. He introduced me to a relationship which does not deny curiosity of soul and spirit, not at all, but implies the experience of order and above-order values of creation and thinking.

That was the experience Boško had. One day, he invited me to visit him. When I arrived, he opened the door of his personal library: he took me to an open, large wooden chest in the corner of his room and said: ”After you read what’s in it, perhaps you will understand what literature is.”

I read it. It lasted a while. I was a third-year gymnasium student, end of the first semester, winter vacation, when Boško gave me a book from the very bottom of the legendary chest. It was the Second Book of Migrations. The circle thus closed with Crnjanski, and before him, according to Boško’s implacable schedule (he even tested me at the beginning), there were Homer and Vuk’s collections of folk poems and stories, then – on the Serbian side – St. Sava, Dositej, Njegoš, Laza Kostić and Laza Lazarević, Rakić and Dučić, Skerlić and Bogdan Popović, Andrić, Jakovljević’s Serbian Trilogy, Drainac, Popa, Raičković… Foreign writers: Hellenic tragedy writers, Cervantes, Goethe, Hugo, Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov, Tolstoy, Tomas Mann, Camus…

Since I had taken the first book, months had passed before I dared to show Boško what I was writing while reading and what I wrote about the books I had read. He kept my notebook. Next time I went to him for new books, he gave me my notes and said: ”In your inscriptions, you only have what, what, but what exists and has a meaning through its how. They are two faces of the same truth, same beauty. Therefore, never contents without form, or vice versa.”

So many years have passed since then! Boško Pavlović is no longer alive; suffering from lung diseases since his childhood, he lived a short life. We often spoke about my studying, but he did not live to see me enroll in the university.

Floors. Decades have accumulated since those times. Gymnasium in Leskovac, Faculty of Philology in Belgrade; editing newspapers and magazines (Student, Symbol, Literary Criticism, Librarian, Letter, Serbian Literary Magazine, Serbian South from Niš, Our Creation from Leskovac); fifty-year-long cooperation with literary periodic magazines and publishers, on the radio, TV, in literary juries… (all that while I was studying, working in the City of Belgrade Library, at the Faculty of Philosophy in Niš). Managing the ”Nikolai Timchenko” Foundation in Leskovac since its establishing in 2005.

Floors. Decades have accumulated since those times. Gymnasium in Leskovac, Faculty of Philology in Belgrade; editing newspapers and magazines (Student, Symbol, Literary Criticism, Librarian, Letter, Serbian Literary Magazine, Serbian South from Niš, Our Creation from Leskovac); fifty-year-long cooperation with literary periodic magazines and publishers, on the radio, TV, in literary juries… (all that while I was studying, working in the City of Belgrade Library, at the Faculty of Philosophy in Niš). Managing the ”Nikolai Timchenko” Foundation in Leskovac since its establishing in 2005.

At the same time, preparing the works of Jovan Skerlić (in five books), Nikanor Grujić, Laza Kostić, Isidora Sekulić, Bogdan Popović, Milan Rakić, Dis, Branimir Ćosić, Bojić, Justin Popović, Rade Drainac…; editing collections dedicated to St. Sava and Ljubomir Nedić.

Then, my own books: monographs, collections of discussions, essays, articles, reviews, criticisms. Anthologies.

Criticism. I entered literary criticism already as a gymnasium student. Since the very beginning, it has been a particular kind of mental activity for me, an activity that sees its entire cognitive, analytical and evaluative work as a unity of different, yet never opposed perceptions.

Criticism. I entered literary criticism already as a gymnasium student. Since the very beginning, it has been a particular kind of mental activity for me, an activity that sees its entire cognitive, analytical and evaluative work as a unity of different, yet never opposed perceptions.

That, of course, does not imply the uniformity of critical approaches and obligations. For example, there is one way to write about the first book of a young author and a completely different about a new book of a literature classic. In the second case, a critic has the entire previous opus of the author, not to mention accompanying moments such as: general literary context, interliterary connections, historical and socio-cultural components.

There is simply no end of the complexness related to literary criticism. I presented it in my essay ”Literary Criticism”, introduction to the book of chosen reviews Criticism as Choice and Conversation with Crnjanski (2016), which represents an intersection of my work in literary criticism until then. I formulated the central thought of the essay as a question: ”Is it allowed to take a text,from which, theoretically and logically, you cannot derive the concept of literary criticism, as critical?”

Problematization and Canonization. The question sounds rhetorical, but it’s not. With its unsaid comprehensiveness, the question takes to the realm of general inspection and evaluation of literature. It opens the problem of general studying of the art of word and thoughts about it.

I placed this subject in the focus of my essay ”Principles of Literary Science”. I discovered that the area is crucially determined by three principles, which I believe fully express the laws on which the basis of all numerous forms of literary studies and knowledge are developing. They are: principle of affirmation, principle of actualization, and principle of problematization. Already at first sight, all mentioned principles represent a key or open a field of a separate literary discipline. Thus, in texts in which the principle of affirmation is confirmed as dominant, we deal with literary criticism for the most part. In works of the literary-historical and comparative-literary direction, however, the principle of actualization prevails. Finally, the third principle – the principle of problematization – is expressed in the deepest manner in theoretical, esthetic, literary-philosophical reconsiderations. (Each of them, at the same time, has its own reverse: opposite of the principle of affirmation is the principle of negation; the principle of neutralization appears opposite of the principle of actualization, and the other, invisible yet omnipresent side of the principle of problematization is the principle of canonization.)

As much as they might seem independent, mentioned principles are not self-sufficient. On the contrary, they are closely interrelated, directed to one another, in constant ”cooperation” and only authors’ ultimate attempts decide on which principle will prevail.

Paths of Literary Science. Attempts of authors are forces that frame the historiographic area of my research of Serbian literature and culture. The area is not single-sided. A simple division puts ideas and their genesis on one side, and persons with their works and meaning on the other.

Paths of Literary Science. Attempts of authors are forces that frame the historiographic area of my research of Serbian literature and culture. The area is not single-sided. A simple division puts ideas and their genesis on one side, and persons with their works and meaning on the other.

The first side is represented by my book Paths of Serbian Literary Science (2020). It is derived from my earlier books: Areas of Literary Spirit (1998), Beginnings and Peaks (2010) and Seeds, Seedlings, Harvest (2015). It has a discussive character, and is heterogenous in a certain sense.

The crucial scientific-literary, methodological setting, which I am guided by in my research, collected in Paths of Serbian Literary Science, is in the question: What do words discover, illuminate, understand, establish, mean in expressions: discover the beginning, illuminate birth, understand lasting, establish values?

Questioning such dilemmas fill the first part of the book. Answers are offered to the following principal questions: did the transition of Serbian literature from Old-Serbian to Vuk’s language cause a break in its development; how was Serbian literature divided into periods and movements; when did literary criticism and when did essays appear among Serbs; what are the beginnings and what was the development of Serbian rhetoric; when was the history of literature born among Serbs as a separate field of study?

The second part of the book includes analytical discussions about scientific contributions of the most significant Serbian critics and literature historians. Light is shed on the stands and works of Zaharije Orfelin, Lukijan Mušicki, Pavel Joseph Šafarik, Stojan Novaković, Ljubomir Nedić, Jovan Skerlić, Tihomir Ostojić, Đorđe Trifunović, Milorad Pavić…

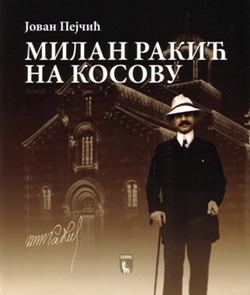

Gligorije and His Establishments. On the other, in no case opposite side of my literary-historical interest, are three monographs, about Gligorije Vozarović, Milan Rakić in Kosovo, Branimir Ćosić (about only one of his books, Ten Writers – Ten Conversations), and a clear work about Belgrade in Serbian literature and culture since the ancient times to the end of World War II.

Establishments of Gligorije Vozarević monograph (1995) is a scientific story about the birth and growing up of civil Belgrade. Who was that Vozarević, forgotten today?

In reestablished Serbia, Vozarević (1790–1848) was not just the first bookbinder, bookseller, publisher (he published the first collected works of a Serbian writer – Dositej Obradović); he was also protector of cultural goods, benefactor, creator and host of the literary home, whose activities led to the opening of our first public library – a home where the thought about establishing the Association of Serbian Education will be born, where Vozarević’s almanac Dove with a Flower of Serbian Literature was established and edited, taken as a role model at the time of establishing the Herald of the Serbian Educated Society. Vozarević came to Belgrade in 1827; he was granted Serbian citizenship only in 1846, after a repeated request and three months before his passing away. A patriot above everything, he did not stay away from politics: he was a man of trust of Ilija Garašanin and the Constitution Defenders.

Rakić in Kosovo. In terms of monographs, my study about Milan Rakić is most important for me. I wrote most part of the first version of the monograph about Rakić in Kosovo at the time of the bombing of Serbia in 1999. The book had three editions up to now (2006, 2013, 2016), the third with the final title Serbian Poet: Milan Rakić and Kosovo. The essential subject of the psycho-biographic, social-historical and literary explorations in the Serbian Poet are Rakić’s years in Kosovo. Who was Milan Rakić in Kosovo from 1905-1912 – that is the main subject of the study. My answer is: he is a Serb with an unbribable national awareness; an erudite with wide knowledge about the past of his nation and the world; diplomat with European views, whose political stands were accepted with equal seriousness both in the Serbian capital city and in foreign palaces; a moralist in whose actions state law and human honor were never in conflict; author of the most wonderful cycle of patriotic verses in the entire Serbian poetry, volunteer in the war for the liberation of Old Serbia, awarded with a Golden Medal for courage by King Petar I Karađorđević. Besides being discussive, the Serbian Poet is, at the same time, a biography, national history and questioning the ethno-psychology of Serbs: the required travel on Serbian history and through it, as well as turning into the character and being of Milan Rakić as a poet, diplomat, fighter, a man who, with his deep and painful, melancholic nature, creation, ethics – colors, illuminates, shadows the past and reality of his time. It is shown that he lived and worked most intensely in a time, for which it is rightfully said that it was ”a time when great people walked the small Kingdom of Serbia.”

Rakić in Kosovo. In terms of monographs, my study about Milan Rakić is most important for me. I wrote most part of the first version of the monograph about Rakić in Kosovo at the time of the bombing of Serbia in 1999. The book had three editions up to now (2006, 2013, 2016), the third with the final title Serbian Poet: Milan Rakić and Kosovo. The essential subject of the psycho-biographic, social-historical and literary explorations in the Serbian Poet are Rakić’s years in Kosovo. Who was Milan Rakić in Kosovo from 1905-1912 – that is the main subject of the study. My answer is: he is a Serb with an unbribable national awareness; an erudite with wide knowledge about the past of his nation and the world; diplomat with European views, whose political stands were accepted with equal seriousness both in the Serbian capital city and in foreign palaces; a moralist in whose actions state law and human honor were never in conflict; author of the most wonderful cycle of patriotic verses in the entire Serbian poetry, volunteer in the war for the liberation of Old Serbia, awarded with a Golden Medal for courage by King Petar I Karađorđević. Besides being discussive, the Serbian Poet is, at the same time, a biography, national history and questioning the ethno-psychology of Serbs: the required travel on Serbian history and through it, as well as turning into the character and being of Milan Rakić as a poet, diplomat, fighter, a man who, with his deep and painful, melancholic nature, creation, ethics – colors, illuminates, shadows the past and reality of his time. It is shown that he lived and worked most intensely in a time, for which it is rightfully said that it was ”a time when great people walked the small Kingdom of Serbia.”

The Greatest Day of His Life. October 1912: Priština had fallen, Kosovo was liberated. The army lined up in front of Gračanica; direction – Gazi Mestan, to bow to Lazar’s Kosovo Heroes. One of the liberators is Milan Rakić.

He later said: ”It was the greatest day of my life”.

Rakić’s telling about the event is lengthy, and he should not be paraphrased. I will, therefore, state another, equally impressive record:

”While the army was on Gazimestan, a young officer was telling Milan Rakić’s verses: ’Forceful knights, without fault or fear…’ An officer from the commit squad is running towards the commander and reporting: ’Colonel, Milan Rakić, the poet whose verses this young officer is reciting, is here, in the squad.’ The colonel orders: ”Milan Rakić, three steps forward!’ Milan Rakić is so excited he cannot move. Then a new order is heard: ’Squad, three steps back, except soldier Milan Rakić.’ Then another command: ’Hip, hip, hurray for poet Milan Rakić!” While entire Gazimestan was echoing from voices, tears were falling down Rakić’s cheeks…”

The young officer who recited Rakić’s poem ”In Gazi Mestan” was Vojislav Garašanin, grandson of Ilija Garašanin, son of Milutin Garašanin.

Genius and Ill Fate of Belgrade. With its stormy history and so changeable fate, always dramatic, Belgrade appears before a concentrated observer now as luxury, now as desolateness; in one moment it is a broken and humiliated slave, and in the next a burning, superior master.

Genius and Ill Fate of Belgrade. With its stormy history and so changeable fate, always dramatic, Belgrade appears before a concentrated observer now as luxury, now as desolateness; in one moment it is a broken and humiliated slave, and in the next a burning, superior master.

Look, everyone is trying to conquer Belgrade, and many things which have been darkness or foggy anticipation yesterday are today appearing in their entire mysterious clearness; in a clear, yet uninterpretable and wonderful mysteriousness. Created to be a lighthouse and monument on the gigantic intersection of roads and worlds, it will remain in foreign and Serbian consciousness, in history and in poems: a city- fortress, a house of holy wars, a city-temple, city-surprise, city-dream. A standing city.

A city with such a genius (genius loci) and such ill fate, whereas none of those two dimensions is never shown alone (they are inextricably connected) – what else could Belgrade be and what can it be, but a natural and deep focus of literary imagination!

Lesson about Returning. A century and nine years after the liberation and returning of Old Serbia to its motherland in 1912, we see Kosovo and Metohija under new occupation. Different acts of the old drama are being written. As if the ancient genealogical law moved from literature to history: comedies are shown one-time, without repeating, tragedies are permanent and return.

Luckily, history is a deceptive category. Truth and justice, faith and knowledge of tomorrow speak differently. Let us look at Serbia. Georges Clemenceau, president of the French government, told one of his sorrows at the Peace Conference in Versailles in 1919: ”At the conclusion of our Conference, I have to, before climbing down from this stage, express my greatest regret because a great historical name is disappearing from the political stage of the world – Serbia.” And he was deeply right: Serbia ”disappeared”, sacrificed to the fatal dream of a monarch about a Yugoslavia. And today? Serbia has returned, fortifying and ascending its intransient being.

***

A Piece of Information

Jovan Pejčić (Bošnjace near Leskovac, 1951). Graduated from the Gymnasium in Leskovac, basic and postgraduate studies at the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade. He was professor at the Faculty of Philosophy in Niš from 1996-2015, where he taught Serbian XX century literature, Serbian XX century poetry, Serbian XX century criticism, Serbian XX century criticism and drama. He published numerous studies and essays in literature and culture history, books of criticisms, anthologies… He prepared and equipped with critical commentaries many Serbian writers, whom he enlisted during this conversation.

He lives and works in Belgrade.

***

Anthologies

From Jovan Pejčić’s voluminous bibliography, for this occasion we will single out some of his unusual anthologies and reviews: Anthology of Serbian Prayers: XIII–XX Century (2000), My Soul Set Off. Prayers of St. Sava / Prayers to St. Sava: 1207–1969 (2002), Anthology of Serbian Praises: XIII–XX Century (2003), Drama Writers from Niš (2004), Poetry and the Holy: Serbian Spiritual Poetry 1 (2019)...

***

Work

In a personally intoned essay ”Window”, I say:

”Days and weeks and months and years are still shaking out time bags of moods on my doorstep. Day and night take turns peeking through my window. What do they find? What do they bring, what do they discover? Bitterness? Sweat? Calls in the night? Serenity? Work? What do they find? Work, work.”